Status epilepticus is said to occur when a seizure lasts too long or when seizures occur close together and the person doesn't recover between seizures. Just like there are different types of seizures.epilepsy also known as a seizure disorder ,epilepsy is a brain condition characteristic by recurrent seizures .seizures are paraoxysmal events associated with abnormal electric discharges of neurons in the brain.the discharge may trigger a convulsive movement,an interruption of sensation,loss of consciousness or combination of these symptoms.in most patients epilepsy does not affect intelligence.

Causes

50% of the cases are idiopathic

Genetic abnormalities such as tuberous sclerosis and phenylketonuria

Perinatal injuries

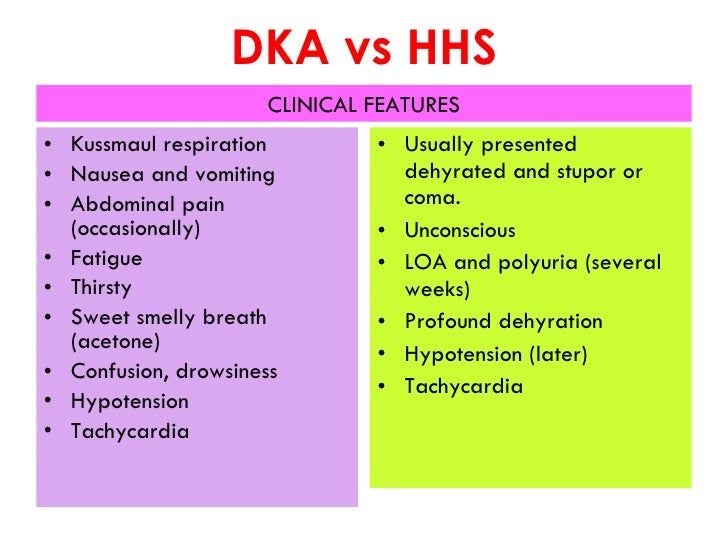

Metabolic abnormalities such as hyponatremia,hypocalcemia,hypoglycemia,

Brain tumours or other occupying lesions of the brain

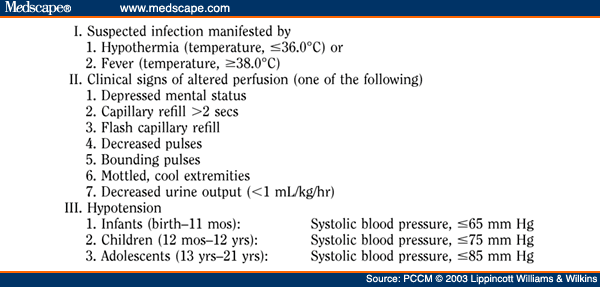

Infection such as meningitis ,encephalitis,or brain abscess

Traumatic injury especially dura matter is penetrated

Stroke

Ingestion of toxins such as mercury,lead and carbon monoxide

Hereditary abnormalities

Different types of seizures

Partial seizures-arising from a localized area in the brain,partial seizure activity may spread to the entire brain,causing generalized seizure.several types

Jacksonian seizure begins as a localized motor seizure characterized by a spread of abnormal activity to adjacent areas of the brain.patient experience stiffining or jerking in one extremity

Sensory seizure-symptoms of sensory seizure include hallucination,flashing lights,tingling sensation,vertigo,de ja vu,and smelling a foul order

Complex partial seizure –usually include purposeless behavior ,including a glassy stare,aimless wandering,like smacking .an aura may occur first,and seizure may last for several minutes.the patient has no memory of his action during e seizure

Secondary generalized seizure-can be simple or complex and can progress to a generalized seizure ,aura may occur first followed by loss of consciousness occurring immediately after 1 to 2 mins.

Generalized seizures cause a genera realized electrical abnormalities within the brain.types include

Absence seizure-common in children,begins with a brief change LOC.seizure last from 1-10 sec and impairment is so breif that the patient can be unaware of it.if not treated properly the seizure can recur up to 100 times per day and progress to generalized Tonic clinic seizure .

Myoclonic seizure-is marked by breif involuntary muscle jerks of the body which may occur in rhythmic manner and breif loss of consciousness

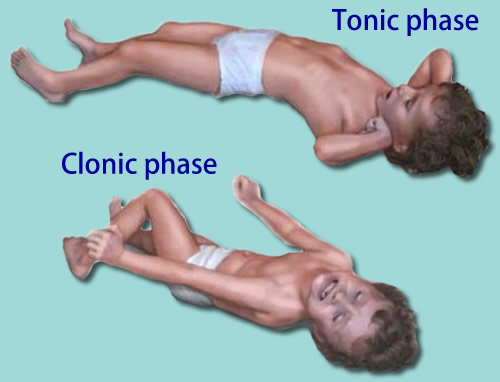

Tonic clonic seizure

• The tonic phase comes first: All the muscles stiffen. Air being forced past the vocal cords causes a cry or groan. The person loses consciousness and falls to the floor. The tongue or cheek may be bitten, so bloody saliva may come from the mouth. The person may turn a bit blue in the face.

• After the tonic phase comes the clonic phase: The arms and usually the legs begin to jerk rapidly and rhythmically, bending and relaxing at the elbows, hips, and knees. After a few minutes, the jerking slows and stops. Bladder or bowel control sometimes is lost as the body relaxes. Consciousness returns slowly, and the person may be drowsy, confused, agitated, or depressed.

• These seizures generally last 1 to 3 minutes.

A tonic-clonic seizure that lasts longer than 5 minutes needs medical help. A seizure that lasts more than 10 minutes, or three seizures without a normal period in between, indicates a dangerous condition called convulsive status epilepticus. This requires emergency treatment.

Investigation and Management

Treating convulsive status epilepticus in adults (published in 2004)

General measures(Early status )

1st stage (0−10 minutes)

• Secure airway and resuscitate

• Administer oxygen

• Assess cardiorespiratory function

• Establish intravenous access

2nd stage (0−30 minutes)

• Institute regular monitoring

• Consider the possibility of non-epileptic status

• Emergency AED therapy

• Emergency investigations

• Administer glucose (50 ml of 50% solution) and/or intravenous thiamine (250 mg) as high potency intravenous Pabrinex if any suggestion of alcohol abuse or impaired nutrition

• Treat acidosis if severe

3rd stage (0−60 minutes)

• Establish aetiology

• Alert anaesthetist and ITU

• Identify and treat medical complications

• Pressor therapy when appropriate

4th stage (30−90 minutes)

• Transfer to intensive care

• Establish intensive care and EEG monitoring

• Initiate intracranial pressure monitoring where appropriate

• Initiate long-term, maintenance AED therapy

Refractory status

Emergency investigations

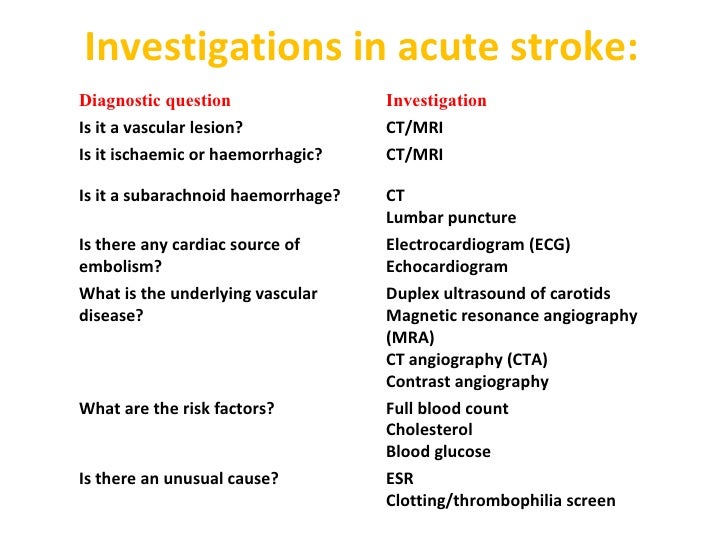

Blood should be taken for blood gases, glucose, renal and liver function, calcium and magnesium, full blood count (including platelets), blood clotting, AED drug levels; 5 ml of serum and 50 ml of urine samples should be saved for future analysis, including toxicology, especially if the cause of the convulsive status epilepticus is uncertain. Chest radiograph to evaluate possibility of aspiration. Other investigations depend on the clinical circumstances and may include brain imaging, lumbar puncture.

Monitoring

Regular neurological observations and measurements of pulse, blood pressure, temperature. ECG, biochemistry, blood gases, clotting, blood count, drug levels. Patients require the full range of ITU facilities and care should be shared between anaesthetist and neurologist.

EEG monitoring is necessary for refractory status. Consider the possibility of non-epileptic status. In refractory convulsive status epilepticus, the primary end-point is suppression of epileptic activity on the EEG, with a secondary end-point of burst-suppression pattern (that is, short intervals of up to 1 second between bursts of background rhythm).

Emergency AED therapy for convulsive status epilepticus (published in 2004)

Premonitory stage (pre-hospital) Diazepam 10−20 mg given rectally, repeated once 15 minutes later if status continues to threaten, or midazolam 10 mg given buccally.

If seizures continue, treat as below.

Early status Lorazepam (intravenous) 0.1 mg/kg (usually a 4 mg bolus, repeated once after 10−20 minutes; rate not critical).

Give usual AED medication if already on treatment.

For sustained control or if seizures continue, treat as below.

Established status Phenytoin infusion at a dose of 15–18 mg/kg at a rate of 50 mg/minute or fosphenytoin infusion at a dose of 15−20 mg phenytoin equivalents (PE)/kg at a rate of 50–100 mg PE/minute and/or phenobarbital bolus of 10–15 mg/kg at a rate of 100 mg/minute.

Refractory status a General anaesthesia, with one of:

• propofol (1–2 mg/kg bolus, then

2–10 mg/kg/hour) titrated to effect

• midazolam (0.1–0.2 mg/kg bolus, then 0.05–0.5 mg/kg/hour) titrated to effect

• thiopental sodium (3–5 mg/kg bolus, then 3–5 mg/kg/hour) titrated to effect; after 2–3 days infusion rate needs reduction as fat stores are saturated

• anaesthetic continued for 12−24 hours after the last clinical or electrographic seizure, then dose tapered.

a In the above scheme, the refractory stage (general anaesthesia) is reached 60/90 minutes after the initial therapy.

References

- Shorvon SD, Trinka E, Walker MC. The proceedings of the First London Colloquium on Status Epilepticus--University College London, April 12-15, 2007. Introduction. Epilepsia. 2007;48 Suppl 8:1-3.

- Kälviäinen R. Status epilepticus treatment guidelines. Epilepsia. 2007;48 Suppl 8:99-102.

- Wilson JV, Reynolds EH. Texts and documents. Translation and analysis of a cuneiform text forming part of a Babylonian treatise on epilepsy. Med Hist. Apr 1990;34(2):185-98.

- Mayo, 2014. Epilepsy. [Online] Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/epilepsy/symptoms-causes/dxc-20117207 [Accessed 18 April 2015].2. Roth, J. L., 2014. Status epilepticus. [Online] Available at:http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1164462-overview [Accessed 17 April 2015].3. Tidy, C., 2012. Status epilepticus management. [Online] Available at:http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/status-epilepticus-management [Accessed 17 April 2015].